Dmitry Orlov rejoins us to discuss his book on the technosphere and how it threatens the environment or biosphere, limits our economic freedoms, and can become weaponized as a political technology. He gives some recommendations on ways to mitigate against the overarching influence of the technosphere.

Transcript

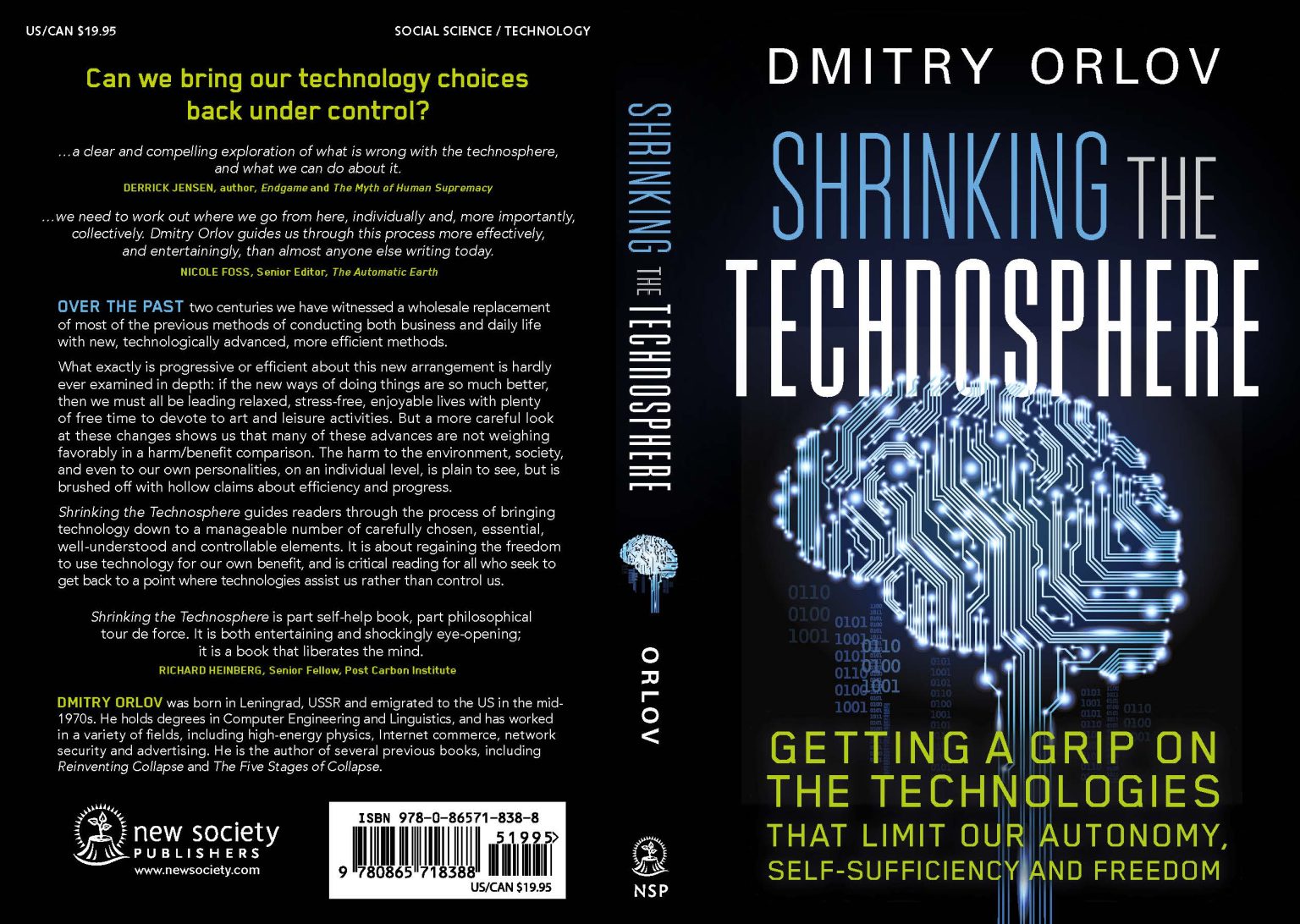

Podcast: Returning to the Geopolitics and Empire Podcast is author Dmitry Orlov. We’ll be discussing his book, Shrinking the Technosphere: Getting a Grip on Technologies that Limit our Autonomy, Self-sufficiency, and Freedom, which touches on ways technology or this thing known as technosphere limits our economic and political freedoms as well as threatens the biosphere and environment.

I’d also like to remind listeners to subscribe to all of our social media and weekly newsletter, all of which can be found at geopoliticsandempire.com, and thank the few of you who have left a tip via Patreon, PayPal, or Bitcoin, and ask new listeners for continued support because it does cost a considerable amount of time, energy, and money to produce this podcast. Without further ado, thanks for coming back on, Dmitry. [spoiler]

Dmitry Orlov: Thank you for inviting me. Glad to discuss this topic.

Podcast: Yeah, and I purchased this book from you a year ago, and only got around to reading it recently. You put to paper succinctly a lot of thoughts I’ve had on this subject of the technosphere, but let’s start with what is the technosphere. The term, for me, evokes different themes, such as the technocracy, the 1930s scientific dictatorship movement, which I suppose is still alive today in some form.

Some people talk about the term globalism, an elite who wield technology to tighten their grip on power, perhaps private corporations who wield greater power than states, such as Silicon Valley, who, at this moment, are purging any anti-establishment voices from their online platforms.

It also, the technosphere reminds me of the Belgian utopian Paul Otlet who wanted to classify the world and create some sort of world city, as well as it evokes images of science fiction dystopian literature in film, such as The Matrix. Could you tell us what is the technosphere?

Dmitry Orlov: Well, what got me thinking about it initially was this thought that there are systems that human being evolve at various points that are not necessarily in their individual or group interest and that these systems behave as emergent intelligences and as agents independent of the human will, that they manipulate people as opposed to people controlling them.

Probably, the first one is agriculture. It made people sicker. It bound them to the earth. It made them unable to move around as they have before, but it increased population density and allowed more powerful systems of control to develop. It gave rise to empires, whereas before, we had basically bands and tribes. That took over.

Then, later on, we had the development of the financial realm and money lending, which was only made possible by agriculture and by the accumulation of harvests, of harvested wealth. Eventually, this way of handling wealth involving money and debt took over and grew out of control, so that money became this necessary evil that people required to keep people at bay.

Then later on, with industrialization and especially with the development of fossil fuels, we had the full development of the technosphere, which is now a realm onto its own, an emergent intelligence that we have no chance outside of that we must allow to take priority over our own interests, even if our basic interest is just elemental survival in terms of not destroying the biosphere or what’s left of the biosphere.

Podcast: Just, again, to clarify that note on your definition of the technosphere. It’s not any sentient being, but I suppose it can be wielded by political elites?

Dmitry Orlov: Yes, well, it can be used to one’s advantage or one’s disadvantage, especially in large groups. For instance, you could make the fatal choice of not industrializing, and then your country will be taken over that has not made that choice, but instead has industrialized and has produced weapons of war at the industrial scale. That has happened over and over again. Attempt to not be part of the technosphere leads to failure.

Another move that people can make is decouple from the global financial system. Well, that leads to revolt eventually because the global system, with all of the injustices that it creates and all of its flaws, allows people to become wealthy. People, when deprived of that ability, will revolt eventually, as has happened all over the place.

People can make decisions on some scale, but in terms of pushing back against the technosphere as a whole, the project is more or less doomed to failure. We are condemned to sort of nibble away at it at the edges to make, basically, lifestyle decisions so that we’re not utterly ravaged by the technosphere, but we can’t banish it altogether.

Podcast: You also say that a technosphere demands homogeneity, and now we’re seeing all this crisis with migration in Europe and Central America where you’re having people from different countries going into European countries. We have this globalization of culture where, here in Kazakhstan, where I am, the most popular restaurant is Kentucky Fried Chicken.

I mean, you go to the malls here in Kazakhstan and the local food chains, when you compare, the KFCs always got this long line compared to the local food chain. What is it about this technosphere that demands a homogeneity of culture, and is the migration crisis part of this push towards making nations homogeneous?

Dmitry Orlov: Well, there are a lot of reasons why these global brands are actually global, and one of them is that they cater to the least common denominator. They care to immature tastes. Children like chicken nuggets. Adult don’t necessarily, but they are forced to eat chicken nuggets because that’s the most universally acceptable fare. There’s a lot of that to it.

In terms of controlling people, the first step from the point of view of the technosphere is to standardize everyone. Instead of having an educational system that basically tries to figure out what each person’s aptitude and talent is, and allow them to develop it individually, which is what produces educated individuals, instead, the effort is to, again, cater to the least common denominator.

For instance, mathematics is dumbed down so that those students in the class who are least capable are able to keep up, and then the smartest students, basically, are deprived of any stimulation in learning math and lose interest. Instead of actually learning how to solve problems, people are taught to fill in circles and multiple choice test forms. That sort of thing.

In terms of the migrant crisis, the effort, which again is very much in line with the interest of the technosphere to commoditize everything including human nature, is to basically posit that there is this universal humanity, and that the universal human rights can supersede just about everything else, and that everybody must be treated the same regardless of how their ancestors have lived and what they have been conditioned to excel at.

Some population groups, they excel at disease tolerance, and others excel at intensive farming. Those groups are not necessarily the same. Some other are excellent at industrial work, and they are disjoint with the other two groups, but everybody is lump into the same group. Everybody has to be treated the same. Everybody is processed based on the same side of bureaucratic principles. That’s the goal.

Podcast: Talking about the technosphere, it reminds me a lot of something Jim Rickards, author Jim Rickards has written about systems or complexity theory. It seems like the more complex a system gets, the more fragile or precarious it becomes. Then it creates these technologies, that it create unintended consequences, which constantly need to be mitigated to prevent the entire system and biosphere as well as technosphere from collapsing.

You’ve mentioned nuclear energy, the problems we’ve seen with that in Ukraine and Japan, GMOs, nanotechnology kind of reminds me of Microsoft Windows updates, which are in need of constant patching for a system that is always failing until one day it can collapse. How fragile is this technosphere itself?

Dmitry Orlov: Well, it’s robust in the sense that it is very difficult to stamp out or destroy, and nobody has the ability to do it. It does not have anything resembling an off switch. It will blindly march forward until something catastrophic happens, but that catastrophe is very much coded into it because although it does possess a certain kind of intelligence, an emergent intelligence, it is not a human intelligence.

The technosphere, to put a too fine a point on it, is an idiot savant. It is very good at growing. Like a cancer, it’s capable of growing, but just like a cancer, it is incapable of seeing whether or not it’s killing its host. The technosphere specifically is completely incapable of seeing physical limits to its growth and expansion. It has absolutely no way of measuring diminishing returns, be it in oil and natural gas extraction, or using the biosphere as a sink, or any of the other problems that develop along the way.

It cannot see physical limits. It is also unable to see the limits of technology. Its basic assumption is that new technology is always better than older technology, but more technology is better than less technology. Then no matter what the problem is, the solution lies in the application of even more technology, even if its technology itself that created the problem, to begin with.

Podcast: To talk a bit of its influence on the biosphere, something that you’ve written about for a long time, the environment and climate change. You give a long list in the book. There’s everything from air pollution, the toxicity, water pollution, the contamination of the plastics, the depletion of so many resources, and as you mention, it’s built into the system. You cite Chris Clugston’s book on technological civilization being a suicide pact. Could you talk about the aspects of the biosphere, how much stress is being put on the environment, where we are in that sense, and where it might go?

Dmitry Orlov: Well, we can see the human footprint, industrial human footprint everywhere and everywhere we look. We can see it from space. We can measure it in a great many ways. We can see it in the California wildfires and the reaction to them. It is almost comical that there is a … News organizations keep talking about the 100-year flood or the 100-year fire, and then a year later, they talk about this year’s fire being the new 100-year fire, et cetera.

We can’t put it. They’re always saying, “This one is for the history books,” and then next year, “Well, throw out the old history book and write a new history book,” because it just keeps getting worse. That’s the comical aspect to it, the aspect of just complete total denial that we’re in runaway mode when it comes to things like forest fires and floods and various kinds of environmental devastation.

The one place where you can definitely see it is in the insurance industry. In all the places in the world where the high standards of the place require property to be insured, in a lot of cases, it’s no longer insurable. The government turns out to be the insurer of last resort. That’s the case with flood insurance in much of the United States these days. The federal government pretty much have to take it over because private insurance would just go bankrupt.

You can see that. You can also see in where devastation results in not very much rebuilding at all. For instance, we know that certain islands, including very large ones, which is in the Caribbean just completely got devastated by hurricanes. How much rebuilding is taking place there? Well, we really don’t know. We don’t hear too much about the success stories of rebuilding in Puerto Rico.

It’s pretty much gone dark as far as I can tell. It’s just not in the news. That’s the patter of complete denial, of not realizing that, wow, we’ve already hit all these limits. We’re way past them. We’re in the age of consequences. We’re not in the age of thinking about what will happen. It’s already happening.

Podcast: Yeah, especially for people who have a family. I just had my first child, and I’m living here 100 kilometers away from the Polygon, the principal nuclear testing site of the Soviets where they dropped 500 bombs. It’s getting really tough to keep a healthy lifestyle because we’re being attacked everywhere from the air pollution, from the water contamination, our foods, genetically modified. It’s a real struggle to watch out for those things.

You were right that part of the inspiration for your book was the speech by President Putin using the term nature like technology is to restore balance between the biosphere and technosphere, and you also write about this mechanism. I guess to do that would be political technologies. You use the example of the United States, how they have really developed their political technologies, and you give examples of how they have used them for bad. It’s a double-edged sword. You say it can be used for good. It can be used for bad.

You name different industries or these political technologies are evidenced from lobbies to media, education, the weaponization of politics, you go a little in-depth with the color revolutions and hybrid warfare. This political technology is kind of like an arm, I guess, of the technosphere. It reminds of the geostrategist Thomas Barnett’s map. I guess he wrote a book called The Pentagon’s New Map.

It depicts the American unilateral version of globalization, and any countries that are experiencing wars and conflicts like Yemen, Syria, and Libya, Iran, they tend to be countries that are independent and not plugged into this system, and so they suffer as a result. Could you talk a bit about the inspiration, President Putin’s talk, the nature-like technologies, and as well as these political technologies, which I assume are part of the solution?

Dmitry Orlov: Well, actually, the fact that I picked up on what Putin said caused me a lot of readers because right as the book came out, Trump got elected, and then all this nonsense started about Russian meddling and the idea that somehow Trump was elected to office because of Putin’s influence as opposed to, say, Hillary Clinton’s absolute, complete incompetence, which is closer to the truth. That cost me a lot of readers. Also, it was a bit of wishful thinking. I think that Putin himself had what I had in mind, but he also is a realist, and the realistic situation is that Russia has to win the technological race against the United States in order to survive.

It cannot just go agrarian, although that’s part of it. Russia has sort of gone in the direction of becoming more agrarian, and it is now the largest grain exporter in the world, the largest grain producer in the world. Grain exports get more money that defense exports at this point, which are also booming. Also, it banned GMOs, which was wonderful. There’s been a great effort to invest in food security. Russia is almost entirely self-sufficient in food at this food. Grapes are, of course, still an important tropical fruit and various other things, but most of the staples are produced domestically.

There’s another part of the thrust which is that the Russians realize that they have to win the technological race, and they have to win it hands down. Part of that is in weapons research, which is going pretty well, especially in the area of defensive weapons, and part of it is in various other fields that are prestige fields that are prestige fields like bioengineering, like nanotechnology, that put Russia on the map internationally, make it a contender, that they’re moving ahead with creating a digital economy.

All government services in Russia are a lot better now, actually, just from a user’s point of view because of all of that commerce is a lot smoother. There isn’t really an effort to push back on the technosphere. There is an effort to co-opt it and use it for the national good of Russia and the Russian people. It’s rather different from what I had in mind, but it’s not all bad.

Podcast: Speaking of the hybrid warfare aspect in that you’ve lost some readers or … I’d also like to mention to listeners that I’ve received a few really strange emails from people as well as a review or two calling the podcast Russian propaganda, and that just happened a week or two ago, someone posted on iTunes, and then I read an article about a week ago from Wired magazine discussing a British information warfare unit whose job is to go online in forums and social media and try to discredit people who have, I guess, discussions, critical discussions like this.

I’m far from a Russian propagandist myself. In fact, I was trying to get on an expert to discuss some elements of criticism of the Russian government. I like to look at all sides, but you try to do your best and see what happens there. I guess you can’t please every listener or reader. There were two interesting tangents or side things you mentioned in your book that I kind of agree with your take on Noam Chomsky and his failure, in a sense, at his … I don’t know if you’d call it a failure, but at his primary profession as a linguist, and then his switch over to politics if you’d care to comment.

Dmitry Orlov: Well, yes, I mean, I don’t really … I don’t particularly feel like I’m picking on old Noam, but I suppose I have an ax to grind because I was a graduate student in linguistics. I was more or less forced to study Chomsky and linguistics. I never actually got very far in it because I couldn’t get a response to my initial criticism of his approach, which I found to be sub-scientific. It was some sort of a fake effort to make linguistics into a science, and that that was just a complete failure, positive mechanisms within the human brain for which there was and still is zero actual physiological evidence, which pretty much angered me.

He pushed ahead with it and he created a sort of linguistics mafia to a point where you couldn’t do any other kind of linguistics in the United States, especially not in Boston. I was just across the river from MIT. There was just no getting away from Chomsky and linguistics, but all sorts of scholarship has a right to exist. It doesn’t have the right to dominate and to squeeze out other approaches that may be more valid.

Podcast: Another interesting part of the book you mentioned, the technospheres continue drive for resources, so it’s assumed, when on Earth, resources are depleted like we see in the movies. We go into space exploration. We have all this stuff like SpaceX and Elon Musk wanting to go to Mars, as well as Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origin, and so this idea to dominate beyond Earth.

You say the Russians are the only ones capable of venturing into space, and that they’ve gone only to low orbit, I suppose, because of the cosmic radiation beyond that, and that we know, I believe, up until 1969, the Soviets, correct me if I’m wrong, were hitting the space first such as first dog into space, first man into space, first spacewalk, which, by the way, on the train here in Kazakhstan, I watched the Russian film Spacewalkers, and I was amazed at the quality of the film, very good. One of the first Russia films that I’ve seen, and I was amazed at the quality.

Then out of the blue, the US lands on the moon in 1969, which you kind of question, and I kind of have doubts myself, and indeed the Russians, just this week, said, I believe, in the future moon mission, they are going to verify the veracity of the US moon landing. I mean, what are your thoughts there, this technosphere going into space as well as the moon landing?

Dmitry Orlov: Well, yes, you can look at the American footage of the moon landing and say, “Where are the stars?” It doesn’t matter if the sun is up or down on the moon. The sky is black, and you can always see the stars, so where are they? I’m not the only one who just calls the whole thing into question. It’s not just these little things that stick out like a sore thumb to anybody who thinks about it a little bit. The director of Roscosmos just recently announced that they want to do a mission to figure out whether the Americans actually set foot on the moon or not.

A lot of people are questioning that. A lot of people are questioning many things that Americans have said or claimed over the years, such as the entire official narrative behind 9/11. Many countries, not just Japan, which I’m not sure what’s going on with that, but many other countries have questioned that narrative at an official level. It would be really nice to eventually figure out just how many times the Americans have lied.

The Americans tend to lie about a lot of things. They lie about their own “civil war” which wasn’t a civil war. It was an invasion of the South by the North. They lie about the fact that it was about slavery. It was not about slavery. Just lots and lots of things about the narratives that Americans have tried to foist on the world just ring false. It makes sense to actually do some work and dethrone these myths.

Podcast: Moving one as well, you described in the book the technosphere being terminally ill, I suppose, depleting resources, the economy being slow in growth as a result of the declining supply natural resources needed for production, this papering over of unpayable debts. It seems more and more people are now seeing the obvious of all these debt bubbles … I mean, a bubble in pretty much everything from pensions to bonds to the stock market to everything. We’re approaching this day of reckoning.

I think you published a book. I mean, you’ve talked a lot about the collapse, the economic aspect, and I think you published a book recently related to that. Can you talk a little bit about what will happen, where we are in the timeline, what do you think it’ll look like if you’ve updated your vision over the years recently?

Dmitry Orlov: Well, what it looks like to me is there is a mad scramble right now for the United States to retain some semblance of its former glory or rekindle it in some way. It’s using the fact that it’s been pumping flat out in the shale oil and gas patch and had a temporary glut, and it’s currently very close to or is the top hydrocarbon producer in the world, but it never made any money doing it. The entire shale industry is going to pretty much go belly up as interest rates increase as they’re bound to.

The depletion rates from all of the existing wells are extremely high. It’s a matter of maybe a year, maybe two years before there is a massive shale crash in the United States. After that, the United States is pretty much done as a hydrocarbon producer and has to become reliant on imports once again. Meanwhile, there’s a temporary glut, but overall, there isn’t really a lot of spare capacity in the world. The world is still discovering much less than its using in terms of hydrocarbon resources. The only exception to that is Russia.

Russia is the only country in the world, really, of any size that’s discovering more resources than its exploiting. That trend is likely to continue. It looks to me like the United States is dreaming of re-industrializing and restarting manufacturing, but that is just not going to happen for any number of reasons, one of which is energy. Another one is the lack of cheap labor force, and a third one is that it’s just got a completely untenable tangle of dysfunctional systems starting with the legal system, it spends too much money on lawyers. The medical system, it spends too much money on doctors.

The transportation, it spends too much money on transportation and energy, very bad infrastructure, no technology clusters that the government has invested any money in, just lots on lots of problems, so it’s not going to happen. At the same time, it seems like Russia is the emerging force that is industrial force in the world that coupled with China will provide Eurasia with a fairly solid industrial basis for maybe a couple more decades, maybe more.

I’ve seen ideas of theories, but they’re not highly theoretical. They’re based on quite a bit of fact. In fact, we also could pave the path to a post-carbon economy based on nuclear energy. In order to become independent of oil, natural gas, and coal in about 50 years, Russia has to start building 10 nuclear power plants a year. It has enough uranium to last maybe 500 years. It is the top uranium processor in the world already. It processes almost half of all the uranium in the world. It’s got a full dance card building nuclear power plants around the world. This is not an untenable, unlikely proposition.

On the other hand, the United States and Western Europe have made all sorts of bad investments. The United States has invested and Canada have invested in very dirty and temporary technology such as tar sands and shale, and Western Europe invested a lot of money in solar panels and windmills that are just basically money eaters, and then there are some really bad examples like Lithuania which closed its only nuclear power plant because it was Russian-built, and Lithuanians don’t like Russians. Now, their energy prices are through the roof, and there’s absolutely no hope of any industry at all in Lithuania. They just basically killed it.

There are a lot of negative examples, and then, on the other hand, there are very sensible developments that are happening around Eurasia in terms of pipelines being laid to Western Europe and to China, plans with Korea, possible plans with Japan if that is ever shaken out, but they all have Russia as the energy and industrial core, which is an interesting development.

Podcast: Yeah, and regarding what you mentioned about the oil, the news today, just today with the Qatar is leaving OPEC, so that’s perhaps a sign of the cracking of the 1970s petrodollar system, and some of the countries looking to pivot perhaps towards the East China, Russia, Iran, and the alternative system being built. You mentioned the nuclear power. I believe Russia recently created their first floating nuclear … Some kind of a boat or floating nuclear power plant.

Dmitry Orlov: Yes, it’s a giant barge with a nuclear power station on it. It can be moved to anywhere in the world and provide a sizeable city with heat and electricity. It needs to be refueled not very often at all. If they put these on stream, I bet there will be a lot of takers around the world.

Podcast: Yeah, a few days ago, I listened to a webinar given by Marin Katusa of Katusa Research who’s a commodities investor, and he was saying how uranium in the next year or two or three, the price of uranium and the uranium miners, that it’s going to be on an up-cycle, so I think that kind of confirms what you’re saying about nuclear power, but what about the concerns of what can go wrong because I think in your book, I don’t know if you’ve changed a bit of your opinion, but the danger you discussed, the money isn’t there to decommission nuclear power plants, and then you have the problems of the water, toxic water runoff. What do you think there?

Dmitry Orlov: Well, there are a lot of problems around the world having to do with nuclear power. There are some in Russia too, but there are basically power plants around the world that have been built by GE and others that there’s really no money to decommission. We can see the problem of doing that with Fukushima. How many decades into the future is that projected to take? That’s a worst case because that’s three meltdowns. There was a success though.

They did manage to move all of the fuel out of the fuel storage tank, which is a good thing. It was heroic, really. A lot of problems with nuclear power around the world, there was really just one horrendous accident that happened within Russia, of course, in the Ukraine with Chernobyl, but there were a lot of lessons learned and a lot of improvement, safety improvements made. Nuclear safety in Russia is almost a religion at this point. It’s very unsafe if done wrong, but there is the possibility of it being done right.

One of the things that Russia is doing now is looking or long-term spent fuel disposal site deep in the bedrock. They’re exploring one particular mountain range. There, the idea is that this fuel will be sequestered safely within a granite bedrock for millennia, and eventually, it’ll just become even more depleted, become safe, and eventually go into a seduction zone and melt into magma, and then circulate inside the planet forever. It will never become concentrated again. As material, it’ll be lost forever, but by then, there won’t even be humans alive on Earth. It doesn’t necessarily concern us.

Podcast: Getting back to the technosphere, and I guess, one of the biggest … Perhaps you could summarize or restate the biggest threats to us from the technosphere. One of the things that concerns me … Well, you call it in your book a single unified global controlling growing disruptive entity existing beyond human reason or morality. One of the aspects, I suppose, of the technosphere, is the technological aspect. We’re really starting to see now the whole surveillance state, no privacy, and we know China has this dystopian Sesame social credit system where people now can’t get on trains or planes.

It was interesting. I think there’s this American entrepreneur of Chinese descent who’s running on the Democratic Party platform for 2020 in the US, who has proposed a similar type of credit system in the US. We have this big surveillance state in the US, the Five Eyes countries, the 14 eyes in Europe. It seems many countries are building it up as well. In India, they’re doing biometrics, and in Mexico, where I’m also a citizen, slowly, they’re starting to do things like that. In Kazakhstan, here, they’re going to digitize the healthcare. Everyone’s health information will be on this one digital card in the cryptocurrencies and the digital currencies. What is your take? Are you concerned with that aspect of the technosphere and how bad can it get?

Dmitry Orlov: Well, there are horrendous opportunities for abuse in all of these systems. People can be herded pretty much like cattle. They become passive. Chances of any sort of productive rebellion can be pretty much neutralized at will, and yet, there are positive aspects to it as well, which is it’s a good way to drive down crime rates. It offers new interesting ways to control human interaction within society, so that, for instance, you can … Just a trivial example.

In Russia, there used to be all of these renegade taxi drivers. When you hailed a cab, you never knew whether you were going to get robbed or raped or whatever. Nobody hails cabs anymore. It’s just not done. Instead, you take out your smartphone and you order a cab from one of the services where everyone is now. Basically, you use some card that’s tied to your internal passport. There’s no hiding. Everything is public record.

There’s really no incentive and a powerful counterincentive for taxi drivers to do anything but offer a good service, anything else that they do is just going to hurt them. That’s not just taxi drivers. That’s every kind of contractor that you can hire. Again, you take out your smartphone, and you can hire anyone to do anything. You can let a person into your apartment to say, “Clean it,” without worrying that they’ll rob you because why would they rob you? They will never get another client again. Those are positive aspects.

The negative aspects all have to do with the evil that giant corporations can do. That’s not an absolute ironclad necessarily. Yes, it’s much more likely to happen in countries where there is no government powerful enough to rein in evil powerful corporations, such as the United States. The US government has minimal control over entities such as Google and Facebook, which have, more or less, melded with the most evil parts of the federal apparatus, the security agencies.

In other countries, that may not be the case. I don’t know where China lies on this continuum, but if you look at how well China is doing relative to the United States, and how quickly China is really outdeveloping and outpacing the United States, how much more they get done, you’d basically have to say that, well, a country that horrendously mistreats its own people is unlikely to achieve such good results.

Podcast: I guess to look at, finally, what are some things people can do to mitigate, I guess, the technosphere? You give an example where going off-grid may not necessarily be a good idea. It can invite problems with the government. I remember that I have a home in Mexico and I was just thinking about in the future trying to go, getting all my electric energy from the sun, going 100% solar.

I mean, I’ve seen people manage to do that in their homes, but there’s a law in Mexico that says you’re not allowed to unplug from the public utility of electricity and go 100% solar if you so wish. That kind of irritates me, but you gave different examples to combat the technosphere. You discuss the formation of a partisan group of people with common beliefs. What are some things people can do, if you want to mention, to mitigate the technosphere?

Dmitry Orlov: Well, getting closer to nature is always a good idea. How close to nature you can get is always is difficult to say. I spent summers in the countryside and have started growing a bit of food. I will probably increase that. Basically, any chance to grab a bunch of land and work it to achieve some level of even partial self-sufficiency is a step in the right direction. A lot such measures can be thought of as insurance against troubled times.

That’s a typical Russian thing to do. A lot of people around here have country houses that they use to grow stuff in the summer, not so much when they don’t need to, but if times get worse, turn worse, they can always resort to that. In terms of going completely off-grid, well, I’ve done that for periods of time by living on a boat where I had a wind generator and solar panels. For periods of time, I could pretty much just unplug from the shore cable, and nobody noticed.

There are a lot of restrictions that have to do with houses that don’t exist for boats for a variety of reasons. For me, living aboard a boat is one of these major, major life hacks that just completely destroys an entire layer of social control having to do with sedentary living, but with people who live in houses, for people who live in houses, there are a lot of problems to sort through if you try to decouple yourself from the technosphere.

Podcast: I guess my final question is you write about the social aspect, which interests me a lot. I’m already able to decouple myself from the technosphere, and I’m planning on doing so, but most people are locked in what you described as that iron triangle, the sedentary iron triangle, the job, the house, and the car, and the debts that come with it, the nine to five job or the taxes, and how difficult it is to move away from that.

I think, oftentimes, people even that are able to move away from that, don’t. I found most people, lately, that I’ve been talking to about this idea of unplugging a bit from the technosphere and doing something different instead of nine to five jobs, they all have this violent reaction. I kind of think of it as a type of Stockholm syndrome, or you call it the robo-path type of person, I think, where people would get offended. Can you talk about that social aspect where a lot of people just buy into this nine to five thing?

Dmitry Orlov: I don’t mean to be rude, but 99% of the people, maybe it’s 98, don’t stand a chance. I’m sorry. They’re just going to be roped into this game until the day they die. It’s pointless to talk to them about it. Probably, that explains the small leadership of my book. I’m lucky that I have maybe 10, 20,000 people who are aware of what I do around the world. That’s a bit of luck. As a percentage of the world population, what is that? Well, it’s astonishingly small.

The people who do try to make a go with it, who strike out and become independent, ditch the nine to five cut their burn rate, diversify their sources of income, maybe turn into digital nomads, maybe combine digital nomadism with growing their own food, which is an amazing way to go. What they have to do is lie to everyone about what they’re doing. Not everybody is such a proficient liar.

You basically have to present a front to the world that is acceptable to them that doesn’t provoke this reaction that you notice where people just hear about you doing this thing, and they just completely decompensate and think you’re some kind of an evil monster just because you don’t want to work for anyone, and you want to live well anyway. That’s just so unacceptable because it undermines who they are, which is a faithful servant.

You have to hide that part of yourself. You can’t just go out and say that that’s what you’re doing. That’s your plan. You’re executing this plan. They will try all sorts of things. They will try to disrespect you. They will try to portray you as some kind of freeloader or as a destructive element, antisocial element. You have to keep that private.

Podcast: Any final thought you want to leave us with regarding the technosphere or anything else?

Dmitry Orlov: Well, I’m very happy that you liked the book and that there is still some interest in it. I decided after I published this book that I probably should just stick to writing essays because it was a big production for me. It required a lot of research, a lot of work. It took a year of my life. The results were that not too many people around the world can accept what I wrote and can make use of it. It was really rather adventurous of me, perhaps too adventurous.

Now, perhaps if people are interested, I’ll pick up this topic in the future. I do these experiments, and some of them work out and some don’t. I’m not sure how this experiment rates in terms of the ones I’ve done, but I hope that this book helps people, and I hope that even if it doesn’t directly lead to some transformative developments in people’s lives, that they find it interesting and intellectually stimulating.

Podcast: I think it’s great that you had that courage to experiment. I mean, we’re not all going to succeed in everything we do, but I can say, I don’t necessarily agree with everything, of course, that was written, but I found it very valuable. It kind of confirmed the path that I was on myself, and you put the paper a lot of thoughts that I had in my mind. You put them out on paper, so I can kind of see them and visualize them. How can people best follow you, your work, and support you as well?

Dmitry Orlov: Well, I run a blog at cluborlov.com. I publish, in general, two articles a week, sometimes a little less. On Tuesdays, I publish a freebie article that everybody can read. On Thursdays, I publish for my supporters on patreon.com. People have to donate as little as a dollar a month to my cause in order to read what I publish on Thursdays. I also started doing videos, and will probably continue doing that as well.

Podcast: You do the videos on the Patreon?

Dmitry Orlov: So far, they’ll probably be private videos on YouTube, but they will be visible to people on Patreon and people with links.

Podcast: Okay. I do urge listeners to go out and get the book, Shrinking the Technosphere, and your past books, you’ve written on collapse. You can get them, I believe, directly from him or through Amazon, paperback, or Kindle. If you do enjoy his work, definitely go check out the Patreon where he has the premium content. If I can ever get my podcast Geopolitics and Empire out of the red, I’d be happy to support you as well, Dmitry. It’s been great talking to you.

Dmitry Orlov: Thank you very much.

[/spoiler]

Websites

https://cluborlov.blogspot.com

Books

https://www.amazon.com/Dmitry-Orlov/e/B001JSB23G/ref=sr_ntt_srch_lnk_2?qid=1544257309&sr=8-2

About the Guest

Dmitry Orlov is a Russian-American engineer and a writer on subjects related to “potential economic, ecological and political decline and collapse in the United States,” something he has called “permanent crisis”. Orlov believes collapse will be the result of huge military budgets, government deficits, an unresponsive political system and declining oil production.

Orlov was born in Leningrad (now Saint Petersburg) and moved to the United States at the age of 12. He has a BS in Computer Engineering and an MA in Applied Linguistics. He was an eyewitness to the collapse of the Soviet Union over several extended visits to his Russian homeland between the late 1980s and mid-1990s.

In 2005 and 2006 Orlov wrote a number of articles comparing the collapse-preparedness of the U.S. and the Soviet Union published on small Peak Oil related sites. Orlov’s article “Closing the ‘Collapse Gap’: the USSR was better prepared for collapse than the US” was very popular at EnergyBulletin.Net.

Orlov’s book Reinventing Collapse:The Soviet Example and American Prospects, published in 2008, further details his views. Discussing the book in 2009, in a piece in The New Yorker, Ben McGrath wrote that Orlov describes “superpower collapse soup” common to both the U.S. and the Soviet Union: “a severe shortfall in the production of crude oil, a worsening foreign-trade deficit, an oversized military budget, and crippling foreign debt.” Orlov told interviewer McGrath that in recent months financial professionals had begun to make up more of his audience, joining “back-to-the-land types,” “peak oilers,” and those sometimes derisively called “doomers”.

In his review of the book, commentator Thom Hartmann writes that Orlov holds that the Soviet Union hit a “soft crash” because of centralized planning in: housing, agriculture, and transportation left an infrastructure private citizens could co-opt so that no one had to pay rent or go homeless and people showed up for work, even when they were not paid. He writes that Orlov believes the U.S. will have a hard crash, more like Germany’s Weimar Republic of the 1920s.

*Podcast intro music is from the song “The Queens Jig” by “Musicke & Mirth” from their album “Music for Two Lyra Viols”: http://musicke-mirth.de/en/recordings.html (available on iTunes or Amazon)