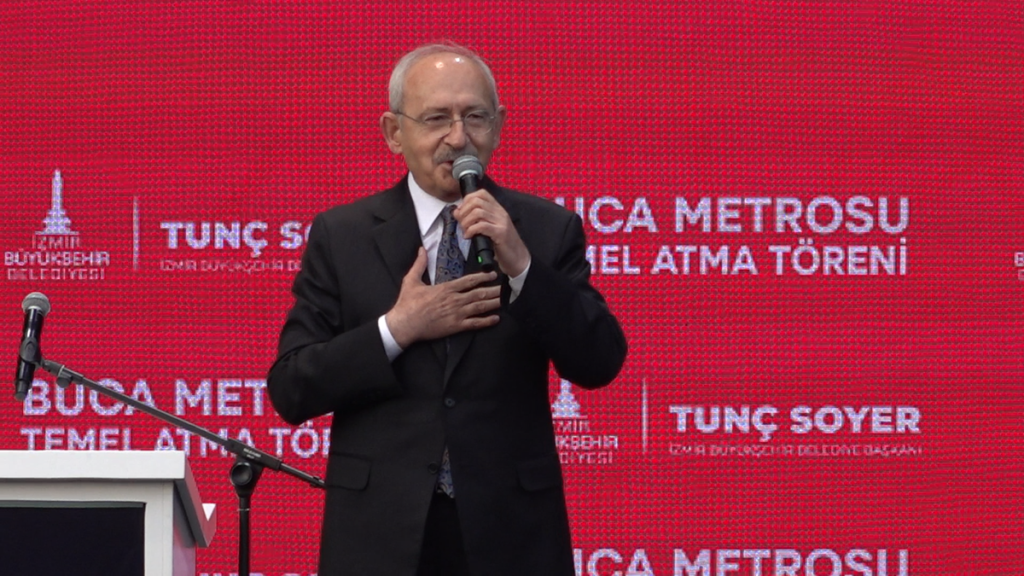

Regardless of the outcome of the “historic” Turkish general elections, Ankara will undoubtedly preserve its leverage over Moscow. Even though the Kremlin indirectly backs Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, Russia is unlikely to change its current political course regarding Turkey even if the opposition leader Kemal Kilicdaroglu comes to power.

While the United States and its allies continue seizing Russia’s assets abroad, and using them to fund Ukraine, Moscow remains busy helping its frenemy Turkey overcome the economic crisis. On May 5, the Kremlin allowed its Turkish partners to delay payment of a $600 million gas bill to Russia until 2024. Moreover, the deal that the two countries have reportedly reached allows for up to $4 billion in Turkish energy payments to Russia to be postponed until next year. Such a move could help a new Turkish government cope with the account deficit that recently hit the highest level since records began. For now, Erdogan could portray the Russian “goodwill gesture” as a “victory” of his foreign policy. However, if he loses the elections – which is entirely possible – be it on May 14 or in the second round, it is Kilicdaroglu that will benefit from Erdogan’s lucrative deals with the Kremlin.

Russia, isolated from the West and bogged down in Ukraine, does not have much room for political maneuvers. If Putin’s “dear friend” Erdogan suffers a defeat, Moscow will have to find a way to develop close relations with Kilicdaroglu, even though the leader of the Republican People’s Party (CHP) may take a more pro-Western geopolitical course. The fact that Erdogan’s major opponent has warned Moscow not to interfere in Turkish elections perfectly indicates that he plans to take a tough stance regarding Russia. Some pro-Kremlin propagandists have already started spreading rumors that “the collective West prepares a Euromaidan scenario for Turkey”, referring to the regime change in Ukraine in 2014. In reality, the West has no rational reason to destabilize its close ally.

There is no doubt that the Kremlin would prefer to continue doing business as usual with Erdogan than to adapt to Kilicdaroglu’s foreign policy priorities. “Better the devil you know than the devil you don’t”, seems to be Russia’s approach regarding Turkish elections. But the problem for Moscow is the fact that most polls suggest that Kilicdaroglu has very high chances to defeat the Turkish President. Thus, if the CHP leader comes to power, and ends Erdogan’s 20-year rule, in order to preserve relatively good ties with Ankara, the Russian Federation will likely have to make significant concessions to the new Turkish authorities.

Turkey, under Erdogan, refused to impose sanctions on Russia. Although Kilicdaroglu is not expected to join anti-Russian sanctions either, he could make additional efforts in helping Ukraine win the war. For instance, according to Turkish foreign minister Mevlut Cavusoglu, Ankara has rejected US proposals to send Russian-made S-400 defense systems to the Eastern European country. But if Kilicdaroglu decides to supply Ukraine with S-400 systems, in exchange for the US-made Patriot missiles, he will strengthen Turkey’s alliance with the United States, and the Kremlin will almost certainly turn a blind eye to such an action.

At home, Putin would use his well-known rhetoric and blame his new partners for “deceiving” Russia. Even if Kilicdaroglu allows US Navy ships to cross the Turkish straits into the Black Sea, Putin is unlikely to take any serious measures against Turkey. Unable to defeat Ukraine, Moscow is not in a position to jeopardize its relations with Ankara, which is why Russia can suffer more humiliations from Turkey in the coming months.

Historically, the two countries fought several wars, and often had extremely opposing views on various geopolitical processes. Under the current geopolitical circumstances, Russian-Turkish relations can be described as a typical situational partnership in which Moscow plays the role of a junior partner. Thus, regardless of Turkish actions that the Kremlin can interpret as “unfriendly”, Russia’s state-controlled nuclear energy company Rosatom will continue building the Akkuyu nuclear power plant in southern Turkey, and Putin will not give up his plans to turn Turkey into a gas hub. But will Kilicdaroglu, who wants to revive Turkey’s EU membership talks, be interested in Russia’s leader’s geopolitical project?

There is no doubt that for the CHP leader, if he wins the elections, the United States and the European Union will be the major pillars of Ankara’s foreign policy. Turkey has the second-largest military in NATO, and is home to Incirlik base, a major overseas post the United States uses to carry out strikes against its opponents in the Middle East. Thus, Kilicdaroglu will almost certainly carefully coordinate his policy vis-à-vis Russia with Washington and Brussels.

Finally, as a result of the Russian debacle in Ukraine, the Kremlin will soon have to face growing Turkish influence in the Black Sea region, including Crimea, where Ankara is expected to play an active role in the foreseeable future.