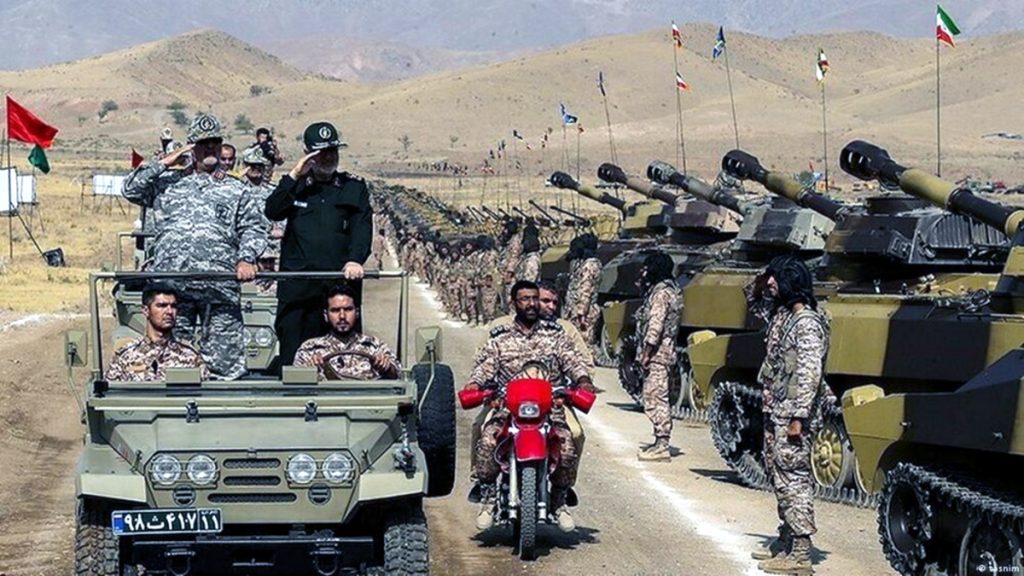

Iran is flexing its military muscles near the Azerbaijani border. The Islamic Republic is expending all forms of cooperation with Armenia, aiming to increase its influence in the South Caucasus, and also to prevent the construction of the Nakhchivan Corridor – a route that would connect mainland Azerbaijan with Turkey via Armenian territory.

Tehran is concerned about the growing presence of the United States and the European Union in Armenia. That is one of the reasons why Iranian leadership recently expressed its dissatisfaction with the European Union’s civil mission that is expected to be deployed to the landlocked nation’s border with Azerbaijan. The Islamic Republic is also alarmed by the growing Turkish influence in energy-rich Azerbaijan, as well as by the strong military cooperation between Baku and Israel. More importantly, Tehran is worried about a potential large-scale unrest in its Southern Azerbaijan province, which is a home to about 30 million ethnic Azerbaijanis—around 16 percent of the overall population of the Islamic Republic of Iran and three times the population of neighboring Azerbaijan.

Given the ongoing protests in Iran, there are fears in Tehran that if the Islamic Republic collapses, neighboring nations’ – namely Pakistani and Azerbaijani – territorial aspirations against Iran will begin to grow. For all these reasons, amid protests in many parts of the country, on October 17 the Iranian military started conducting massive drills near Azerbaijani border. Reports suggest that the most noteworthy element of the exercises so far has been the practice of crossing the Aras River using pontoon bridges, which Iranian media said was the first time the forces have drilled on that technique. Does that mean that the Iranian military is preparing to eventually cross the river and invade Azerbaijan?

Iranian drills could be interpreted as Tehran’s response to the Caucasian Eagle 2022 joint military exercises held on October 11 in Georgia’s Mukhrovani Training Center by the Special Forces units of Georgia, Azerbaijan, and Turkey. Tehran, however, assures Baku that its drills were pre-planned and that Azerbaijan was notified in advance, “taking into consideration the friendly and brotherly relations between the two countries”. In reality, relations between the two Shia nations are neither friendly nor brotherly. Baku and Tehran have completely opposite geopolitical interests in the region. Azerbaijan seeks to get a land connection with its ally Turkey, while Iran, as well as the United States and the EU, is trying to fill the gap caused by Russia’s preoccupation with the war in Ukraine, and increase its influence in Armenia in order to create a counterbalance to Turkish-Azerbaijani-Pakistani axis.

Thus, by holding military drills near Azerbaijan, Tehran is simply demonstrating that it “controls the situation”. At the same time, Tehran is sending a message to Baku that any attempts to take advantage of the instability in the Islamic Republic will result in a harsh Iranian response. Azerbaijan, for its part, continues to strengthen political and military ties with Turkey. On October 20, the two countries’ presidents, Ilham Aliyev and Recep Tayyip Erdogan, met in Azerbaijan’s city of Zangilan, a place that was under the Armenian control from 1993 until 2020. The two leaders opened a new international airport in Zangilan, located only three kilometers from the Iranian border.

Meanwhile, some 30 kilometers West from Zangilan, the Islamic Republic’s Foreign Minister Hossein Amirabdollahian opened the Iranian Consulate General in Kapan, in Armenia’s Syunik province. Iran is the first country to establish a diplomatic mission in Syunik – strategically important region through which the Nakchivan Corridor should pass. Yerevan, however, firmly opposes any idea of the construction of such a transportation route.

“Neither in writing nor verbally Armenia did not make any commitments about providing a corridor. All those who claim that Armenia has promised something like this are presenting their wishful imagination as reality”, Armenia’s Ambassador at-Large Edmon Marukyan wrote on Twitter on October 19.

Such a rhetoric, however, could undermine Armenian positions in Nagorno-Karabakh where the future of the Lachin Corridor – linking Armenia with the self-proclaimed Republic of Artsakh – depends on the Russian peacekeeping forces. Russia is not in a position to help Armenia – Moscow’s nominal ally in the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) – in case of a potential escalation in the region, which means that Yerevan risks suffering another defeat against Azerbaijan.

Armenia, however, aims to strengthen its ties with Iran, and is allegedly seeking to purchase weapons from the Islamic Republic. It remains to be seen if the United States – given Washington’s recent attempts to increase its influence in the South Caucasus – would welcome such a move. That is why the landlocked nation has to balance its ties with the West, and its ambitions to have Iran as a de facto ally against Azerbaijan.

Baku, on the other hand, quite aware of Armenia’s difficult position, could use the opportunity to resolve all of its territorial disputes with the neighboring country, and achieve some of its ambitious geopolitical goals in the region. Even if Azerbaijan invades Armenia, which does not seem very probable at this point, the EU will not impose any serious sanctions on the energy-rich country, as the bloc remains heavily dependent on Azerbaijani natural gas. The EU’s or even CSTO’s mission on Armenian-Azerbaijani border is unlikely to protect Armenia if Azerbaijan, for whatever reason, decides to raise the stakes seizes portions of Armenian territory. Thus, from Armenia’s perspective, Iran remains the only foreign actor that can help Yerevan to preserve its sovereignty, especially in the south of the country.