The invasion of Ukraine has ended the era of globalization the Russian elite enjoyed since the collapse of the Soviet Union. Although Russian oligarchs will be able to continue purchasing Western-made luxuries, the Kremlin’s overall geopolitical vector is expected to shift eastward.

Russia’s so-called special military operation in Ukraine has brought Western sanctions and economic isolation to the Russian Federation. Moscow is now forced to look for ways to bypass sanctions and increase business ties with “friendly countries” – those that have not implemented any restrictions in their cooperation with Russia. However, some very close Russian allies have openly stressed that they will not help Moscow evade Western sanctions imposed over the Kremlin’s actions in Ukraine.

“Kazakhstan is not part of this conflict. Yes, we are part of the Eurasian Economic Union but we are an independent state with our own system, and we will abide by the restrictions imposed on Russia and Belarus. We don’t want and will not risk being placed in the same basket”, said Timur Suleimenov, the deputy chief of the Kazakh presidential office.

On the other hand, Kazakh President Kassym-Khomart Tokayev claims that he supports Russia’s initiative on implementing the Greater Eurasia Project – initially proposed by Russian President Vladimir Putin in 2016 in order to bring the economies of the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) closer to China.

“Russian President made an absolutely rational proposal to involve interested countries in the integration process. Here we have China’s project of the New Silk Road, as well as other countries that really express interest in joining the processes of integration in the Eurasian space” Tokayev told the plenary session of the Eurasian Economic Forum held in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan, on May 26.

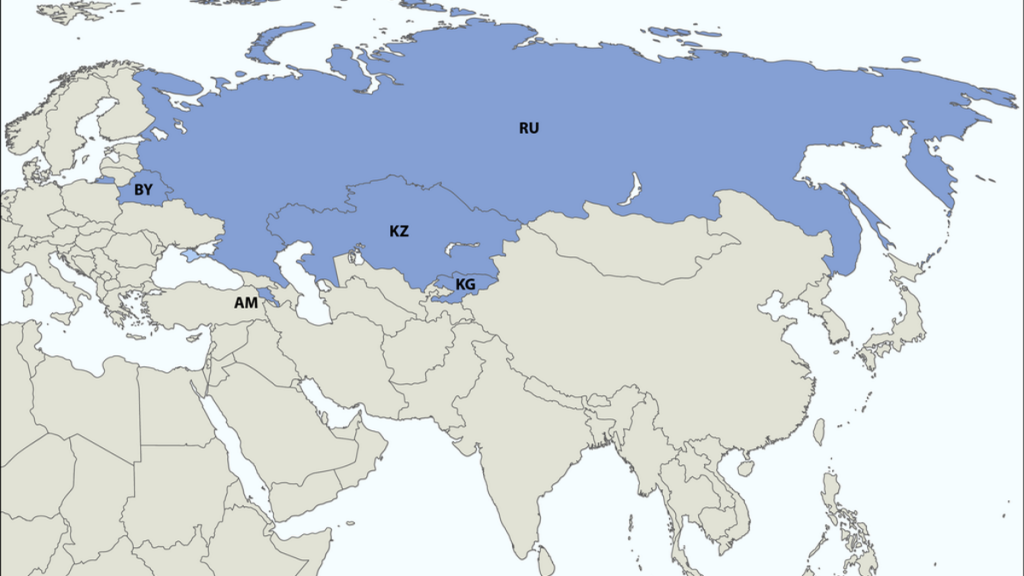

Besides Russia, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan, other members of the EAEU are Armenia and Belarus, while Uzbekistan and Cuba have become observer states in 2020. Iran is reportedly interested in joining the Eurasian Union, which is why Tehran and the EAEU signed an interim free trade agreement in 2018. The document was extended it in 2021. Still, from Russia’s perspective, Iran’s potential membership in the EAEU would, at least to a certain extent, limit Moscow’s influence in the organization where the Islamic Republic would be the second-largest country.

Presently, the EAEU heavily depends on the Russian economy, given that Russia accounts for about 80 percent of the entity’s GDP. In 2020 figures, Russia’s GDP stood at $41.5 trillion, while the closest EAEU economy was Kazakhstan at $170 billion. Thus, it is not surprising that the Russian Federation has benefited the most from its membership in the Eurasian Union, while other members have achieved relatively modest economic progress since they became members of the Moscow-led bloc.

Politically, however, Russia is struggling to increase its influence in almost all EAEU countries. With the exception of Belarus, not a single member of the Eurasian Union has supported Moscow’s “special military operation” in Ukraine. Moreover, Russia seems to have a hard time preserving its cultural influence in the region.

“We lost Ukraine because we paid attention to the economy, energy and political leaders, and not to education and culture, language problems and the impact on youth”, said Vladimir Shamakhov, the director of the North-West Institute of the Russian Presidential Academy of National Economy and Public Administration.

In his view, Moscow now has to create “a new education system that will be implemented not just in Russia, but in other EAEU members as well”.

“What exactly will be the new education system is still unknown. But I believe it is necessary to create not a Russian education system, but a Eurasian one, with the participation of all member countries of the Eurasian Economic Union”, Shamakhov stressed.

Now that Russia is expected to leave the Bologna Process, launched in 1999 to create a universal standard for higher education across Europe, the Greater Eurasia Project could serve as an alternative to the current model of globalization in which the Kremlin played an important role.

Shamakhov’s claims that a new education system should be based on Eurasian, rather than on Russian values, indicates that the Kremlin does not aim to build Russia as a nation state, but rather as the leader of Eurasian integration.

Indeed, the Eurasian Union has potential to eventually become much more than a purely economic alliance. However, given a very slow and not particularly efficient integration process, as well as Russia’s weakened positions in the global arena, it is rather questionable to what extent the EAEU member states will be willing to surrender their sovereignty to this supranational entity.